I’ve been teaching stress management for years, and when I ask people what stresses them out most, they usually tell me it’s all to do with juggling too much, or because they are worried or anxious about something like money, one of the kids, something happening at work, an ageing parent and the like.

I’ve been teaching stress management for years, and when I ask people what stresses them out most, they usually tell me it’s all to do with juggling too much, or because they are worried or anxious about something like money, one of the kids, something happening at work, an ageing parent and the like.

Interestingly, some of the latest research on the topic of stress suggests that some of the causes of stress are much more insidious than we might think.

(Long post alert – grab a cup of tea!)

The Fight or Flight Stress Response

Back in the day, we were taught that stress is basically a fight or flight response in response to a threat. It’s something we share with most, if not all, other animals, and it’s vital for our survival. In days of old when we were nomadic hunter gatherers, and threatened by large, dangerous animals with big teeth and claws, the fight or flight response tuned our bodies so we could deal with ravening beasts who saw us as dinner, or as a threat in our own right.

This is still the case. However, neuroscience is starting to reveal that the stress question is rather more complicated than we used to think.

The Stress Surprise

According to the latest research, from a motivation perspective we are hardwired to avoid threats and the possibility of pain, and gravitate towards anything that gives us a reward. In itself, that’s not particularly surprising. What is surprising is what we perceive as threat. This is important, because it is the threat, or at least the belief that we are under threat, which causes us stress.

The big surprise for most of us is that the brain interprets our social needs ‘in much the same way’ as it interprets social needs, and ‘social threat’ in the same way as it interprets physical threat. The writer and researcher David Rock has come up with a model to help us understand and remember all this: SCARF – Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness and Fairness. In this post, I’m just going to cover the Status aspect and how it relates to stress.

Quick Tour Of The Brain

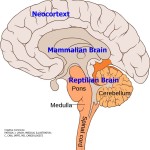

First off, let’s take a brief tour around the brain. It’s important to understand a bit about brain anatomy, because certain parts of the brain shut down when we are stressed in order to conserve energy for the important job of fighting or running away, and it’s the thinking part that is most affected.

Our brains are divided into 3 parts – the so-called ‘triune brain’. The oldest, most basic, part is often referred to as the reptilian  brain, because it’s the bit we share with the reptiles. It beats our heart, manages our body temperature and our balance, and carries out other basic functions which are essential to our successful survival. It also houses the RAS (Reticular Activating System) – a sort of 24/7 radar alert system – that pays attention to what’s going on in our environment without us having to be aware of it. The reptilian brain is very much active when we are stressed. Then there is the limbic or mammalian brain, a bit more sophisticated and home to the emotions. An important component of the limbic system is, or rather are, the amygdala: almond shaped structures which process ‘fear-inducing stimuli’, i.e threats. It’s the amygdala that help us learn what is threatening, so we can avoid it next time round.

brain, because it’s the bit we share with the reptiles. It beats our heart, manages our body temperature and our balance, and carries out other basic functions which are essential to our successful survival. It also houses the RAS (Reticular Activating System) – a sort of 24/7 radar alert system – that pays attention to what’s going on in our environment without us having to be aware of it. The reptilian brain is very much active when we are stressed. Then there is the limbic or mammalian brain, a bit more sophisticated and home to the emotions. An important component of the limbic system is, or rather are, the amygdala: almond shaped structures which process ‘fear-inducing stimuli’, i.e threats. It’s the amygdala that help us learn what is threatening, so we can avoid it next time round.

Then there is the neo-cortex – the thinking, learning part of the brain. This is the area where we process language, abstract thought, imagination and the like. Other animals (like dogs and rats) have a neo-cortex, but it is not nearly as well developed as in humans. This is the part that is most likely to shut down when we are stressed, because you don’t need language, or abstract thought, or imagination to run away from a large, hungry beast. However, you do need muscles, and muscles need well-oygenated blood to function, so that’s where the blood (and the oxygen) go. And this is why, when we are very stressed, we literally can’t think.

What Neuroscience Tells Us About Threats And Stress

Now we’ve travelled round the brain, let’s get back to SCARF.

As I’ve said, the brain doesn’t really distinguish between physical and social threats. But what constitutes a social threat? And why does it matter? And what can we do about it?

One of the most important social threats is a threat to status. ‘Status’, I hear you cry, ‘what rubbish, I’m not status conscious.’ Oh, but you are. We all are. It’s hard-wired in. If you look at studies of animal groups, particularly primates, the characters at the top of the pecking order get first dibs on food and the like. The very weak, sooner or later, are left to fend for themselves, they get the left-overs, and many of them die, so relative status is important for survival. You don’t need to be at the top of the social order, but you definitely don’t want to be at the bottom. When someone says or does something that makes us feel less confident, or as if we have done something wrong, it can feel as if our social status is under threat, and we respond just as we would if this were a physical threat: the stress response kicks in. At some level we ‘worry’ that we are being kicked down the social order, and that potentially means death.

Bullies unconsciously know this: social exclusion is a powerful tool in the bully’s weaponry. However, you don’t have to be a bully to threaten those around you without even realising it. Those little criticisms which we throw out unthinkingly can, over time, start to feel like a social threat to our friends and loved ones, as well as our colleagues. Similarly, remarks like ‘could I just have a word’ can become threatening, particularly if the ‘word’ is always a critical one. When it comes to threat, we are very quick to learn, thanks to our ever-vigilant amygdala. For some people, just talking to their boss feels socially threatening, because it makes them conscious of their own lowly status.

How Does This Help Us Deal With Stress

For some people, just knowing how the social threat aspect of stress works helps them develop strategies to manage it. Some of the most useful tools can be found in CBT (Cognitive Behavioural Therapy) and NLP (Neuro-Linguistic Programming). You can even use self-hypnosis to re-programme your own behaviour. Resilience training can also help, because it teaches people how to develop new strategies for dealing with perceive threats. Many stress management courses focus on time management, but the truth is this is often akin to moving the deck-chairs on the Titanic. Time management can be useful if the stress levels aren’t too serious, but when you are stressed to the point of being unable to concentrate, you really don’t need the added stress of keeping blow-by-blow accounts of how you are spending your time.

Where this information is particularly valuable is in our roles as friends, parents, lovers, bosses, colleagues and the like. For example, we can offer positive comments to boost another person’s sense of social status. We can hold back on the little criticisms. We can think about how we use phrases like ‘can I offer you some feedback’.

People feel that their status increases when they feel they are learning and improving and someone notices, so praise your kids when they actually seem to have absorbed something at school! Public acknowledgement can also raise our sense of status, so giving praise, and creating opportunities for people to succeed is an excellent strategy for reducing stress.

Stress is an unavoidable aspect of daily life. It’s necessary for our survival, and even for our motivation. It often comes in unexpected forms from unexpected directions. However, there’s plenty we can do to reduce both the impact stress has on us, and the impact we have on others.

If you need help with dealing with stress, please contact us for more information.